Trading in pollution permits has blossomed into a big business. The system has produced little benefit for the climate. Even so, the alternatives are barely discussed. A chapter from the Coal Atlas.

To limit the amount of greenhouse gas they churn out, the European Union and various other countries have set up emission-trading schemes. Based on national plans these schemes set the total amount of emissions permitted for the affected industries. The operators of these industries can trade permits among themselves. If an operator emits less of the offending gas than allowed, it can sell the permits that it does not need. An operator that emits more gas has to buy additional permits. This system is supposed to provide a financial incentive for reducing emissions. A company that discharges too much gas has to pay more, while one that cuts its emissions can sell permits to pay for the investments needed.

Seventeen such schemes have been set up around the world, and several more are planned. The biggest is the European Emission Trading Scheme. National schemes exist in Switzerland, New Zealand and South Korea; California, the Canadian province of Quebec, Tokyo and several provinces in China have regional schemes. By 2016, some 6.8 billion tonnes of CO2 equivalent will be covered by such measures.

Emissions trading is based on two premises. First, that it limits the emissions of climate-killing CO2. Second, the scheme aims to stimulate investments in protecting the climate. Sadly, it does neither, as can be seen from how the European scheme has performed.

Under heavy lobbying pressure, the EU set the permitted limits for emissions far too generously, and subsequently cut them back too slowly. From the start, the number of permits has been too high, so the prices they have attracted have been too low to stimulate investment in climate protection. In addition, governments have given away permits for free to the most climate-damaging firms, handing them a big financial windfall.

The recipients, including large power generators, took advantage of the situation and sold their excess certificates. Between 2008 and 2012, the ten major beneficiaries profited by 3.2 billion euros. The energy companies must now bid for the permits they want, but lavish exemptions mean that nearly all polluters in the industry still get them for free. Plus, all companies continue to benefit from the transfer of their surplus permits from earlier trading periods. The steel firm ArcelorMittal, for example, will not have to buy any extra permits before 2024.

In theory, emissions trading is capable of reducing CO2 emissions while still allowing entrepreneurial freedom. In practice, however, the trading scheme has not made a significant contribution to climate protection. This is because of the so-called offset credits that companies have been able to buy in large numbers outside the emissions trading scheme. The reasoning goes like this: it does not matter where in the world the CO2 emissions are cut, so rather than investing lots of money in reducing their own emissions, European companies may as well contribute to initiatives that save emissions elsewhere. But how would the initiatives have performed without this financial support? Between one-third and one half of such projects result in no additional benefit because the investments would have been made anyway. Further, these offsets reduce the pressure in Europe to switch to products that produce fewer emissions.

Emissions trading has long become a business opportunity for the financial industry. Simple, direct transactions between buyers and sellers of pollution permits have become rare. For institutional investors, carbon dioxide is now something akin to a raw material, and is traded in the form of various financial products. But because of the oversupply of permits, trade is virtually at a standstill. Scandals involving tax fraud, including those involving the Deutsche Bank, have revealed the susceptibility and vulnerability of the system. HM Revenue & Customs, the British tax authority, believes that a large share of emissions trading is laced with fraud.

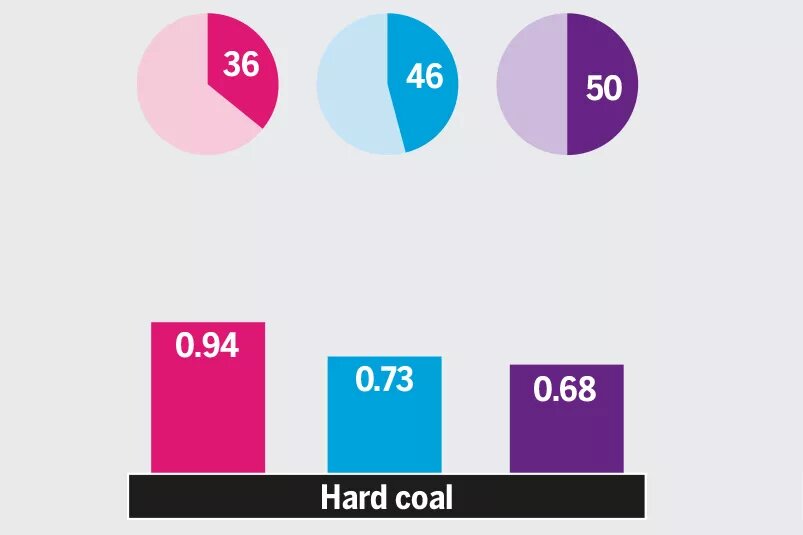

Through offsets, oversupply, the economic crisis of 2008/9 and the associated erroneous forecasts, the number of excess permits in Europe has risen to over two billion. As a result, the price of CO2 is far too low. Combined with low prices for coal and high prices for natural gas, coal has boomed. Between 2010 and 2013, emissions from this sector rose by six percent. The CO2 surcharge was not high enough to make power generated from less-harmful natural gas competitive with the more-harmful coal. To achieve the desired effect, the trading scheme needs stricter limits on emissions.

An alternative approach, used by several states in the United States, as well as by Canada and Britain, is to impose CO2 standards on power plants that use fossil fuel. Since 2013, the British government has set a minimum price for CO2 and annual emission budgets for new power plants, equivalent to the emissions from a modern gas-fired plant. Since 2014, France has charged a tax – albeit a small one – on fuels. The rate will quadruple until 2020. It is also possible to force old power plants offline by applying a technical criterion to their efficiency. The Netherlands will bring in a minimum requirement that will ensure that four older plants will shut down by 2017.

Explicit criticism of emissions trading as the “wrong solution” came recently from an unexpected quarter. Pope Francis wrote in his encyclical “Laudato si” that emissions trading gives rise to a new type of speculation, but does not serve the cause of cutting greenhouse gases.